I’m Linda Haaland, a second-year PhD student at NTNU in Trondheim. I study the interplay between tectonics and geomorphology, and have a background in structural geology and tectonics. This summer, after a year of planning and cancelling travel due to the pandemic, I finally got to visit Svalbard in search of the most valuable thing a young researcher can get: data.

Beginning my PhD just before the pandemic broke out has faced me with some challenges. The most severe of them is that I have been unable to conduct the fieldwork that I need for my research. I also haven’t had many opportunities to meet other researchers, colleagues or, let’s be honest, people. My stay in Svalbard allowed me to do all these things, intensely so, for almost five weeks.

Upon arrival in Longyearbyen, some extremely helpful and friendly colleagues at UNIS offered to take me along to Sassenfjorden where they were working the very next day, as they had room for one more person on the boat. I accepted happily, and spent the day learning lots about the local stratigraphy and the area in general. I also picked up tricks related to doing boat-based fieldwork, which turned out to be very useful over the course of the next month.

The first part of my field campaign was a five-day trip to Billefjorden with the research vessel Clione. The work there was to study the Billefjorden Trough, a half-graben basin, uplifted and beautifully exposed in the mountainsides surrounding Ebbadalen. My job was to investigate how present-day topography relates to the rifting processes that formed the basin. We spent long days in the field, measuring structures and documenting landscapes, hiking across glacial rivers and up into the mountains. At the end of it, I was completely exhausted, but also more excited and motivated to work on the project than I had ever been before.

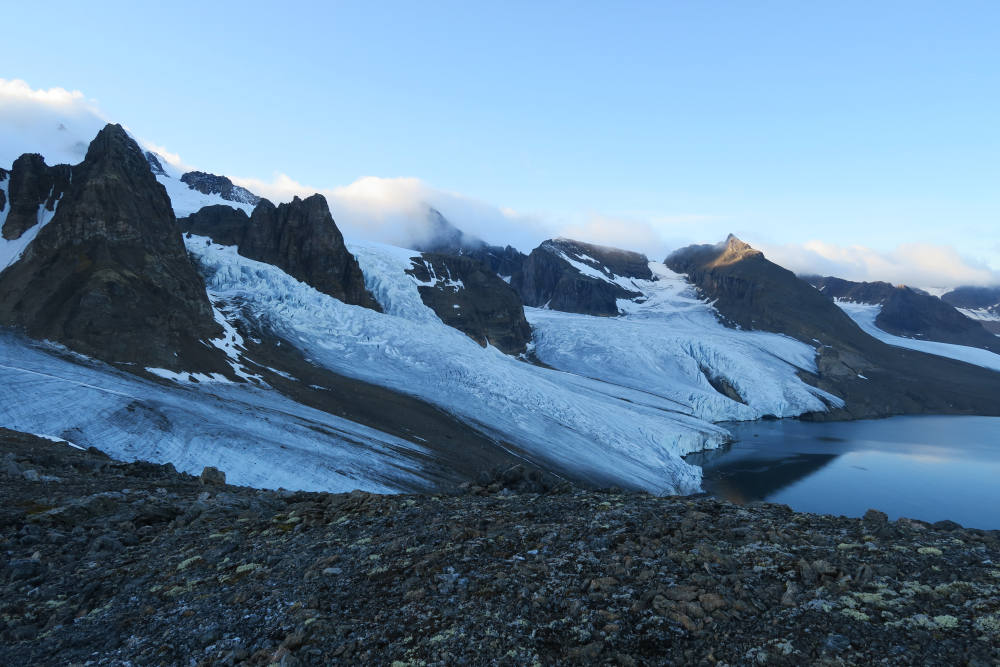

The second campaign was a two-week stay in Hornsund, onboard the much larger research vessel Ocean B. On this trip, I mostly functioned as a field assistant for others, which turned out to be a fantastic experience. I was able to help others collect that sweet, sweet data they needed, and in the process, I learned a great deal about my colleagues’ projects, and got to see the beautiful area that is Hornsund. And when I say beautiful area, I mean beautiful area. There were sharp peaks plunging into the ocean between calving glaciers and, of course, fascinating geology around every corner.

The third and final part of my fieldwork was a 10-day trip to the westernmost part of Svalbard on the island of Prins Karls Forland. During this campaign, the goal was to collect structural and sedimentological data from the Forlandsundet Basin in order to propose a tectono-sedimentary evolution for the area. The Forlandsundet Basin contains sedimentary rocks of Eocene to Oligocene age, some places highly deformed, allowing us to study the specifics of how the rifting process took place on the western margin of Svalbard. The time in Prins Karls Forland was well spent, and slowly I filled my notebook with page after page of the data I’d missed since I started my PhD. The campaign to Forlandsundet was, like the two previous campaigns, a perfect experience. We had great weather, wonderful company, awesome wildlife encounters, and the most stunning views of the field season so far. And once again I disembarked in Longyearbyen, completely exhausted, but ever so motivated to get back to work again.

One of the main advantages to doing fieldwork on Svalbard, is the great outcrop exposure. Little vegetation, as well as usually excellent stratigraphic control, make it easy to find areas of interest. Also, much of the fieldwork is done in the company of exotic wildlife including whales, walrus, seals, reindeer, and arctic fox, as well as crowds of busy birds trying to finish all their bird-related business before winter returns. The main downside to fieldwork on Svalbard is that you always need to keep in mind that some of this wildlife could be dangerous. I am of course talking about polar bears. This means always keeping a rifle and flare gun at hand, and always remembering to look around from time to time. Luckily, we didn’t encounter any problems with polar bears during our stay, and only saw a peaceful mother with her two cubs from the safety of the boat, through binoculars, just the way one hopes to see polar bears on Svalbard.

Two years’ worth of fieldwork, all conducted from expensive research vessels in difficult-to-reach locations would not have been possible without the generous help from the DEEP research grant. Thank you so much for a wonderful opportunity, I am so happy to finally have proper field data to work on, and I am feeling more motivated than ever to get back to the office!