My PhD work is based in Oslo, investigating the sedimentary and volcanic system of the later stages of the Oslo Rift evolution. For anyone that has tried to undertake detailed fieldwork in heavily forested regions like Oslo you will be well aware of the difficulties of working with patchy outcrop exposures and moss and algae covered rocks. It is difficult to say the least, and we often lack greater context for what we see in the field. One of the key uncertainties is the origin of a 40m thick deposit of interbedded gravelly sands and sandy gravels. The deposit is composed almost entirely of volcanic fragments with many beds dominated by pumiceous material. Ask a sedimentologist and you will likely get an assured answer that this is an alluvial conglomerate; ask a volcanologist and the answer will likely be that this is a lithic rich series of ignimbrites. These are in fact the answers I have received form experts in the respective fields.

How can we determine the origin of such enigmatic deposits where we no longer have

contextual information such as proximity to a volcanic centre or morphology of the

deposit. We can look at the details of individual beds and study thin-sections for features that lend support to one interpretation over the other, but whilst this brings us closer to determining volcanic or sedimentary origins at the scale of individual beds it has proved to be far from conclusive. We can consider the transition from a primary volcaniclastic deposit to a volcanic-clast dominated alluvial deposit as a continuum, and that the deposit in question lies somewhere on the continuum, hence, a better understanding of the key end-member styles will aid our interpretations. That is where Tenerife comes in; one of the primary type localities for much of the work that went into Michael Branney and Peter Kokelaars research on the sedimentation of ignimbrites. Not only are the deposits fantastically exposed, easily accessible, and well preserved, they are also extremely diverse and spatially correlated between proximal, medial, and distal deposits.

The first days in Tenerife were spent on reconnaissance with two of my PhD advisers in tow. We covered a lot of ground, looking at a full spectrum of volcaniclastic deposits and occasional alluvial deposits where we could find them. Sometimes these reconnaissance days don’t feel (or sound) like much work, but they are important for setting a plan for the detailed fieldwork that follows. In these first days we looked at the full spectrum of deposits on offer in Tenerife and settled on key locations that showed features that were broadly similar to some outcrop features we find in the Oslo deposits.

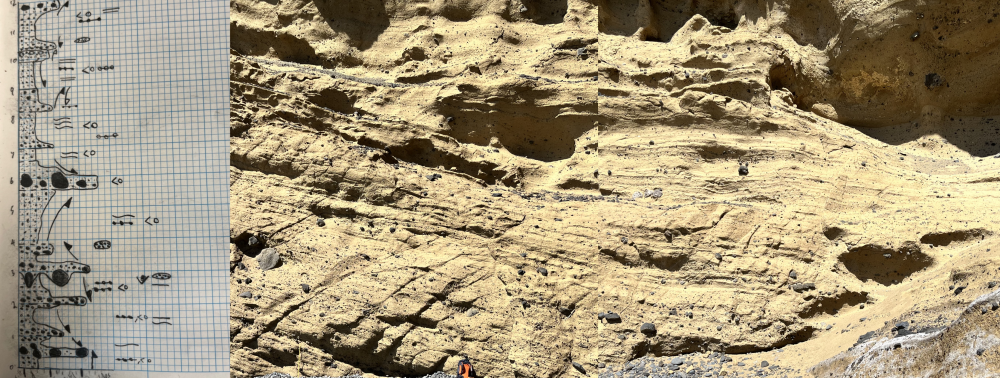

After these few reconnaissance days the others had to depart and I was left to start on

some detailed stratigraphic and photographic outcrop logging, capturing as much of the variability across a range of volcaniclastic deposits as I could. In each outcrop we wanted to capture the details of bed thickness, bed contacts, bedding features such as crossbedding and clast grading, clast properties such as rounding and composition, and features of the fine-grained portion. Graphical logs of this information are combined with detailed photo logs as shown below. These make for easily comparable records when we conduct fieldwork in the Oslo region.

Ten days, twenty logs and ~900 photos later the fieldwork came to an end. Although it

was a relatively short trip, the experience gained over the course of this fieldwork was

invaluable and will have a considerable contribution in our interpretation of volcanism in the Oslo Rift. This trip was only possible with the generous contribution of funds from the DEEP research grant and for that I am incredibly grateful.